Over Christmas, we were waiting around for a turkey on the stubborn route to getting cooked when the topic of this warm winter surfaced. Someone said, “It’s that El Nino thing,” and hence the discussion began about this strange no-snow Montana winter. I said something like, “The last time I remember a really warm winter with no snow was when dad and I rode into the Little Belt Mountains in January – I think maybe 1983.”

Officially, it seems, we are in an “open winter” with high temperatures setting records in some areas of the state and bare roads to drive, for the most part. Old timers defined this as a winter that stays consistently warm and no snow cover. To make it even more odd, we’ve had an occasional rain in, like, the middle of December. What is up with that?

The Essentials of an El Nino

An El Nino event is curious and worth exploring, in case it might affect the 2024 Montana crop. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) characterizes El Nino as “unusually warm ocean temperatures in the Equatorial Pacific.” They occur every two to seven years and are launched by a shift in the trade winds. (“Two to seven” sounds a bit random, until you consider the reliability of any given forecast, right?) Scientists measure three months of Pacific Ocean temperature data before they can determine, and thus declare, an El Nino event. Not to be confused by its colder cousin (La Nina), the trend causes increased rainfall across the southern tier of the U.S., drought along the West Pacific such as Australia, and drier and warmer conditions for the Pacific Northwest including Montana.

El Nino Origin

Since the 1600s, the Peruvians would note a repetitive change in their fish populations. They called it “El Nino de Navidad,” meaning the Christmas boy because they found that this reduction in fish would peak in the twelfth month. Coastal Ecuadorian and northern Peruvian fishermen suffered from the effect as fish populations would lower drastically. The trend also brought flooding to western South America and north into Baja. As per example last August, Hurricane Hilary landed in southern California. It was the first tropical storm for that region since 1939 and it caused major flooding as part of our current El Nino event.

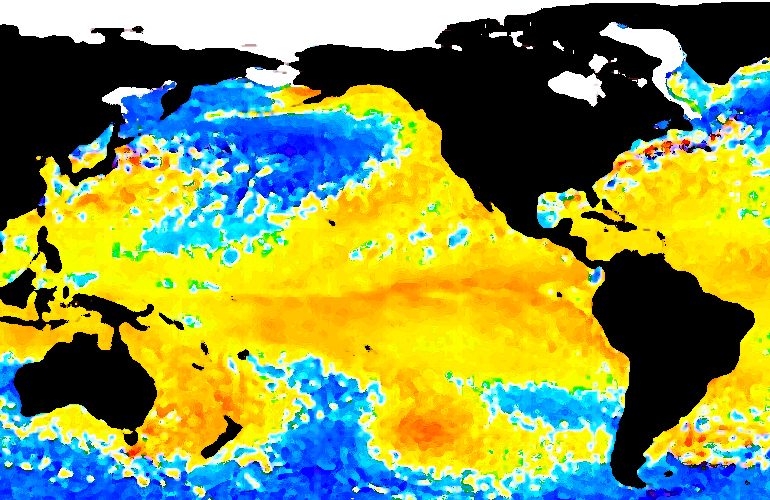

In the 1930s, climatologists determined that El Nino occurs simultaneously with a change in air pressure over the tropical portion of the Pacific Ocean. This pressure shift causes a domino effect: westward-blowing trade winds weaken along the Equator causing Pacific waters to increase in temperature; trade winds push these warm waters eastward; and then the United States begins to look like the map to the right.

Current Conditions

Last June, NOAA declared the arrival of El Nino and expected it to be moderate to strong. It looks like they were spot on. Those of you diehard Farmer’s Almanac followers are probably irritated with their predicted snowy bliss of skiing and snow forts for this year. Apparently, they didn’t get the NOAA memo! This week, Showdown Ski Area at Neihart began offering free lift tickets to skiers with season passes from certain other Montana slopes. Mountain snowpack recordings are anywhere from 33 to 50 percent of normal at this time in Montana, which is not good news for irrigators.

As I write this, we are entering into a severe cold front planning to impress us with well below zero temperatures into the weekend. It doesn’t sound like it will last long, nor is it bringing much snowfall with it. AccuWeather’s long-range forecast shows that El Nino will continue its course with moisture arriving late March followed by a wet spring. If they are correct, and that’s a big IF, we could see moisture through the spring planting season.

Planning Ahead

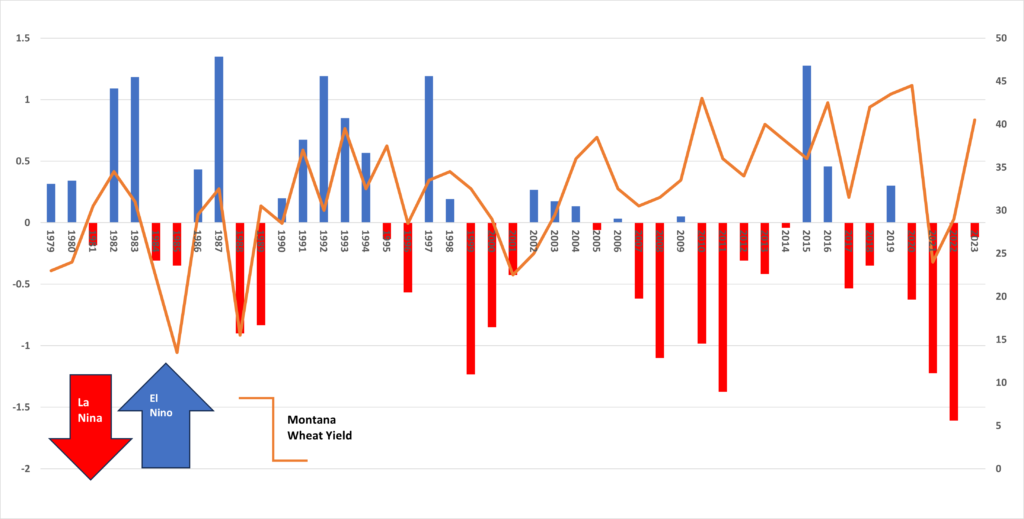

This graph exhibits every El Nino since the 1950s; it is a predominantly consistent display of the consistency of El Nino. Unless something really odd happens, it looks very likely that we will roll out of El Nino by the end of spring. Curious about how producers are reacting, we called a few folks to see how their winter wheat is surviving and if they have plans to adjust spring plantings or other activities.

Leonard Schock, Vida

“In our area we have had 5.5 inches of measurable precipitation since mid-September. The late October snow of 13-14 inches soaked in way better than I would’ve imagined. But that doesn’t go north of the river, and probably doesn’t reach to Circle. For winter wheat, sometimes we raise it and sometimes we don’t. Last fall, the timing of the rains was about when we would’ve started planting winter wheat, so we held off.

Right now as I sit here in my pickup, I’m looking at two fields: one had continuous crop spring wheat which last year yielded 39.6 bushels/acre, and the other was yellow peas that produced 39.4 bushels/acre. We have no set rotation; we tend to wing it a bit more. We like about 15 percent in oilseed, 15 percent yellow peas, and then the rest in spring wheat.

I am thinking our spring wheat planting will be mid-April, about the same as we normally do. We don’t worry about an event like El Nino too much because you just never can plan too far ahead with the weather.”

Will Roehm, Great Falls

“We are in great shape with moisture from the end of September and early October. Our winter wheat looks really good; everything came up. We haven’t had winter kill yet, but we’ll see what happens this week. Winter kill is a very real thing, and there’s nothing you can do about it. Obviously you try to pick varieties that have winter kill resistance like Bobcat which is rated for “winter hardiness.” There is a concern with the lack of snow cover.

We don’t plant spring wheat. Instead we plant canola and malt barley in the spring. If we can get in barley a week earlier this year than normal, we might do that. Our barley is going good and we make malt specs most of the time. 2020 was the first year we planted canola and we were surprised by good yields. That year, we had lost all of our winter wheat crop so canola was planted into summer fallow.

Summer weather will tell if we have an early harvest. I don’t really try to plan because we just don’t know what it will do. I would rather have timely rains than quantity rains as six inches of timely will do more than 13 inches all at once. Dad always said, ‘With one inch of rain the fourth of July, we’ll have a barnburner.’”

Todd Hansen, Gildford

“This year is the least amount of winter wheat we’ve ever seeded. The late drought last year, plus losing to the wind two years in a row made me quit planting as much winter wheat. Up here, if we don’t have it in the ground by about the 15th or 20th of September, winter kill is a very real possibility.

I honestly don’t plan to seed any spring wheat or barley. For us, the plan is to plant lentils and mustard in the spring. They have been worth a lot more per acre and mustard is a better fit for my area over canola.

With regard to this weather, we really don’t adjust much. We will try to get out there as soon as we possibly can this spring. I would rather make a mistake by being too early than being too late. However, people have been talking about having no wind this winter. It’s been eerily calm which is not normal, as generally we have wind with warm temps. But the thing is, you know that’s going to bite us at some point. Maybe next spring we can’t get the sprayers out because it’s too windy?”

What To Expect?

U.S. El Nino history appears to have a positive influence on a cropping season as it begins and ends, covering two cropping years. That would make sense according to our 2023 season, where moisture levels were mighty and harvests just as strong for most in production agriculture. Sam Anderson, our market development director, laid Montana historic yield data over the same timeline of El Nino. In most cases with El Nino, it appears that the year following its close will be dry. If that comes true, then the summer of 2025 could be drier and warmer. Based on this yield record Sam created, I’m not sure that a La Nina (colder winters) guarantees lesser yield performance. Probably worth another study!

Final Words

These three producers I visited with have learned by experience that decisions made using other variables, whether it be input costs or crop rotation or variety advantages, are the better route rather than worrying about a weather event like El Nino. I must admit, I had to give myself a tad bit of credit. Out of the last 50 years, the other strong El Nino was–1982-83. Perhaps my memory is not as rough as I thought!

Sources: What are El Nino and La Nina? National Ocean Service, NOAA; NOAA ENSO November 2023 Update: This Winter’s El Nino is Officially a Strong Event, WeatherBrains, 11-10-23; El Nino is a Phenomenon, US Geological Survey Communications and Publishing; NOAA declares the arrival of El Nino, National Weather Service, NOAA, 6-8-23; Bomb Cycles, Atmospheric Rivers and a Hurricane, San Francisco Chronicle 12-29-23; What is an El Nino Winter and How is it Impacting Montana? Alania Margo, KTVQ, 1-2-24